Executive Summary

Digital forensics is a branch of forensic science that encompasses the recovery and investigation of digital content related to a crime. Originally digital forensics was used solely in computer related crimes. As computer crimes evolved and expanded into the areas of cyber bullying, child pornography and trademark violations; digital forensics has proven an effective means for arbitrating disputes of evidence provided to the judicial system. The mass adoption of digital content like social media sites, cloud-based storage and digital media has placed digital forensics as a common element in the field of forensics for nearly every crime. Moreover, forensics may also play a role in the private sector; such as during internal corporate investigations or intrusion investigation (a specialist probe into the nature and extent of an unauthorized network intrusion).

The example below was taken from a true story involving a teenager who, sadly ended her own life due to cyber bullying. Digital forensics was used as a key activity for identifying the cyber bullies and the extent to which they carried out their damaging impact to this young woman’s life. The story is based on factual events; however, the names of the individuals and details of the cyber investigation are fictitious. The intent it so to provide an example on how digital forensics is used in a real-world case and how the responsibilities and actions of the digital forensics investigator plays a role in the investigation.

Digital forensics is a branch of forensic science that encompasses the recovery and investigation of digital content related to a crime. Originally digital forensics was used solely in computer related crimes. As computer crimes evolved and expanded into the areas of cyber bullying, child pornography and trademark violations; digital forensics has proven an effective means for arbitrating disputes of evidence provided to the judicial system. The mass adoption of digital content like social media sites, cloud-based storage and digital media has placed digital forensics as a common element in the field of forensics for nearly every crime. Moreover, forensics may also play a role in the private sector; such as during internal corporate investigations or intrusion investigation (a specialist probe into the nature and extent of an unauthorized network intrusion).

The example below was taken from a true story involving a teenager who, sadly ended her own life due to cyber bullying. Digital forensics was used as a key activity for identifying the cyber bullies and the extent to which they carried out their damaging impact to this young woman’s life. The story is based on factual events; however, the names of the individuals and details of the cyber investigation are fictitious. The intent it so to provide an example on how digital forensics is used in a real-world case and how the responsibilities and actions of the digital forensics investigator plays a role in the investigation.

Forensics Report Summary

On January 19th, 2017, the Assistant District Attorney (ADA) for the State of Texas retained Jeffrey Howell (hereinafter “investigator”), a sole practitioner to investigate the digital evidence in the case involving Victim (hereinafter “Victim ”), Defendant 1(The State of Texas vs. Defendant 1, 2017) and Defendant 2(The State of Texas vs. Defendant 2) (hereinafter “defendants”). The scope of the digital evidence to be investigated is limited to Victim’s computer, Facebook account and Match.com account (hereinafter “evidence”). [1]

The investigator’s objective for this project are to:

Readiness

This section will describe the processes and policies in place to ensure the investigator is adequately prepared to receive, examine and document the evidence. In this section, the investigator outlines the readiness factors that qualify him, his tools, laboratory, software and hardware for the examination and reporting of the evidence. According to Forensics Readiness Guidelines, Forensic Readiness is having an appropriate level of capability in order to be able to preserve, collect, protect and analyze digital evidence so that this evidence can be used effectively: in any legal matters; in security investigations; in disciplinary proceeding; in an employment tribunal; or in a court of law (The National Archives, 2011).

Appendix A – Forensic Readiness Checklist identifies ten widely accepted principles for investigators to adopt to be adequately prepared for an investigation. The appendix contains the principles, specific activities taken for this case along with the dates of completion. In summary, the investigator has a readiness policy in place, has invested in the proper storage and handling of evidence per ISO 27001 standards, requires that he and anyone on his staff are current in forensic certifications and will immediately escalate to the proper authorities the discovery of evidence that shows an endangerment to lives. Further, any equipment, software, tools used in this investigation are updated to the most current release versions of the hardware and software published by the vendor or in the case of open source, is frequently updated with the latest published releases.

Evaluation

The Evaluation phase comprises of the task to determine whether the components identified in the objectives of the case indeed relevant to the case being investigated and can be considered as legitimate evidence (Patel and Kapse, 2015). In this phase of the case, there was one laptop computer that contained data on the hard drive along with two external sources of data; Victim’s Facebook account and her Match.com account. All three sources are believed to be relevant to this case. Victim’s cell phone was considered, however, in the initial evaluation, there was no incremental evidence to be obtained from what was already believed to reside on Victim’s laptop, Facebook and Match.com accounts.

There are two risks involved with the collection and preservation of evidence; these risks can be classified in two categories: legal risks and risks to integrity. Integrity risks are usually associated with factors related to technology.

Examples of integrity risks include:

Legal risks related to this case involve the 4th Amendment, Due Process and evidentiary reliability

On January 19th, 2017, the Assistant District Attorney (ADA) for the State of Texas retained Jeffrey Howell (hereinafter “investigator”), a sole practitioner to investigate the digital evidence in the case involving Victim (hereinafter “Victim ”), Defendant 1(The State of Texas vs. Defendant 1, 2017) and Defendant 2(The State of Texas vs. Defendant 2) (hereinafter “defendants”). The scope of the digital evidence to be investigated is limited to Victim’s computer, Facebook account and Match.com account (hereinafter “evidence”). [1]

The investigator’s objective for this project are to:

- Forensically evaluate the evidence to try to determine the events that led to Victim’s suicide and;

- Identify the perpetrators responsible

- Providing an opinion of the chain of custody for evidence collected prior to the investigators receipt of the evidence

- The Investigator’s analysis was limited to only the source materials received from the Police Department and did not include interviews of defendants (Coalfire Systems, 2015)

Readiness

This section will describe the processes and policies in place to ensure the investigator is adequately prepared to receive, examine and document the evidence. In this section, the investigator outlines the readiness factors that qualify him, his tools, laboratory, software and hardware for the examination and reporting of the evidence. According to Forensics Readiness Guidelines, Forensic Readiness is having an appropriate level of capability in order to be able to preserve, collect, protect and analyze digital evidence so that this evidence can be used effectively: in any legal matters; in security investigations; in disciplinary proceeding; in an employment tribunal; or in a court of law (The National Archives, 2011).

Appendix A – Forensic Readiness Checklist identifies ten widely accepted principles for investigators to adopt to be adequately prepared for an investigation. The appendix contains the principles, specific activities taken for this case along with the dates of completion. In summary, the investigator has a readiness policy in place, has invested in the proper storage and handling of evidence per ISO 27001 standards, requires that he and anyone on his staff are current in forensic certifications and will immediately escalate to the proper authorities the discovery of evidence that shows an endangerment to lives. Further, any equipment, software, tools used in this investigation are updated to the most current release versions of the hardware and software published by the vendor or in the case of open source, is frequently updated with the latest published releases.

Evaluation

The Evaluation phase comprises of the task to determine whether the components identified in the objectives of the case indeed relevant to the case being investigated and can be considered as legitimate evidence (Patel and Kapse, 2015). In this phase of the case, there was one laptop computer that contained data on the hard drive along with two external sources of data; Victim’s Facebook account and her Match.com account. All three sources are believed to be relevant to this case. Victim’s cell phone was considered, however, in the initial evaluation, there was no incremental evidence to be obtained from what was already believed to reside on Victim’s laptop, Facebook and Match.com accounts.

There are two risks involved with the collection and preservation of evidence; these risks can be classified in two categories: legal risks and risks to integrity. Integrity risks are usually associated with factors related to technology.

Examples of integrity risks include:

- Crashing the hard drive - The investigator needs to ensure that copying the hard drive, if not performed correctly, could cause the hard drive to crash during the cloning phase.

- Overwriting volatile memory – when performing live data collection, the introduction of any new user can force the Operating System (OS) to reallocate memory to accommodate the new process or user request on the target system. This could overwrite relevant evidence that was stored in the previously allocated memory.

- Ensuring overall data integrity – It is a widely accepted practice to clone the original source of digital evidence like a hard drive. However, if this is not performed correctly, the reliability, completeness, accuracy and verifiability of the analysis could be compromised and fail to meet the evidentiary standards of the courts (Keneally and Brown, 2005)

Legal risks related to this case involve the 4th Amendment, Due Process and evidentiary reliability

- The 4th Amendment protection against unreasonable searches and seizures - There is a significant risk to the admissibility of digital evidence if; one, the search warrant requested is outside the boundaries of the relevant components of the case and two, if the bit-streaming method of collecting evidence violates the intended scope of the warrant like the collection of intellectual property, privileged data or privacy protected data (Keneally and Brown, 2005).

- Constitutional Protections of Due Process – There are two core elements in Due Process; the right to have notice and the opportunity to appeal. In terms of digital evidence collection, the right to appeal is a significant risk. If the evidence collected is damaged or erased, this would leave the defendant with little to no opportunity to challenge the evidence or hire their own expert to testify on their behalf. This was proven in United States V. McClure where the defendant’s clothes were destroyed and no longer available for the defendant to challenge the evidence (United States v. McClure, 2003). The evidence must be preserved in its natural state.

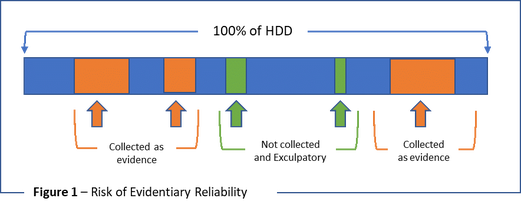

- Evidentiary Reliability – As technology progresses and specifically as the capacity for storage increases, it is becoming less practical to examine 100% of a storage device like a hard drive. The economics, resources and timing for an investigation are too constrained. Therefore, techniques to extract only relevant elements of the overall storage media obtained during evidence collection is becoming the norm. However, the reliability of this evidence can be called into question. Figure 1 below illustrates a hypothetical use-case of overly restricting the search for evidence on a hard drive. Evidence that is believed to be relevant is typically extracted through free text searches and other means but can potentially omit exculpatory evidence which can be challenged by the defense, potentially rendering the collected evidence as inadmissible.

The Investigator’s initial evaluation determined the following measures would best be undertaken to mitigate risks outlined above:

- Extra care will be taken to evaluate the specifics of Victim’s computer before any cloning of data. Specifically, the investigator will look to the amount of data that currently exists on her drive versus the capacity of the drive. If the drive is already at full or close to full capacity, additional precautions will be made prior to cloning the drive.

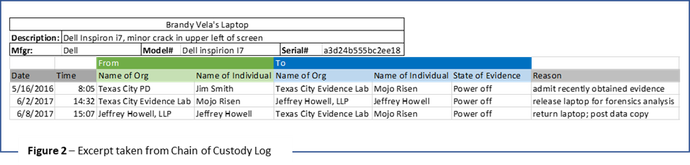

- In this specific case, Victim’s laptop was originally submitted into evidence with the power turned off. Further it was submitted to the investigator in the same state (power off) several days after its last known use. Therefore, there would be little the investigator could do to recover data residing in volatile memory if it existed and certainly not within the time, resources and budget allocated to this investigation. See figure 2.

- The investigator will use a widely accepted practice of using Hash keys (both MD5 and SHA-1) to register all digital evidence with a unique identifier. This will be performed against the original and the clone to show the clone perfectly matches the original. See Appendix B - Hash values associated with the digital evidence

- In terms of mitigating legal risks, the investigator will implement the following:

- 4th Amendment – Victim’s parents provided the police with Victim’s computer with their consent to access the computer, files, Facebook account and Match.com account. Additionally, it has come to the investigator’s attention that a formal warrant was issued by the court granting access to Victim’s Facebook account and her Match.com account. Further, the court has stated there are no objections to the evidence relied upon herein.

- For mitigating both risks of violating Due Process and overall evidentiary reliability; the investigator will examine 100% of Victim’s hard drive. The volume of data is estimated to be small enough to review well within the time, resources and budget of the case.

Evidence Collection Procedures

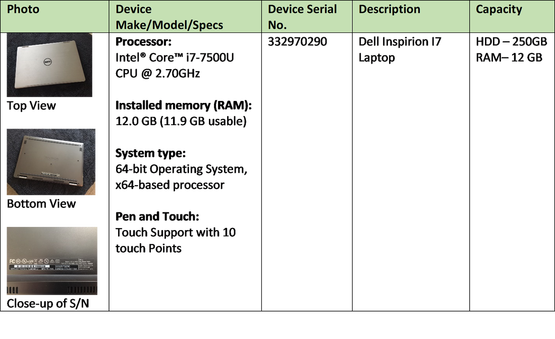

The Investigator employs industry standard tools and techniques throughout handling, processing, and analysis of the evidence. A sealed UPS envelope was received into investigator’s lab on June 2, 2016 at 10:05 AM PST. A Chain of Custody was established upon opening the package. The package contained one laptop computer sealed in an anti-static bag. Details about the enclosed media are included below, see Figure 3.

Figure 3 – Physical Evidence Received

Once received, Victim’s laptop was stored and locked in the laboratory HVAC controlled locker while the laboratory was being set-up for the forensic investigation.

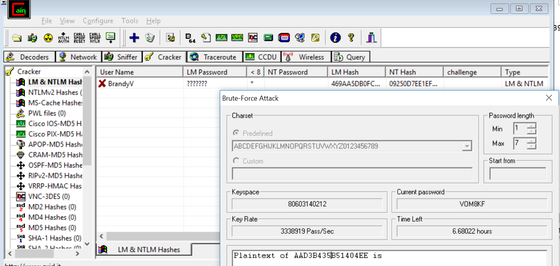

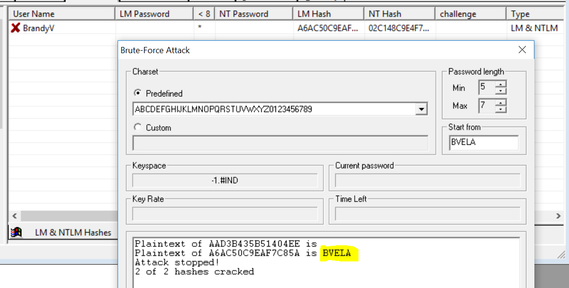

Once the lab was prepared, the investigator removed Victim’s laptop from the storage locker, provided power and attempted to boot the laptop. The laptop required a password. The investigator utilized the Caine and Abel software version 4.9.56 to recover the password. The first attempt involved the use of a dictionary to identify the password, unfortunately this was not successful. The next attempt utilized a brute-force process and after 5.5 hours, the investigator successfully recovered the password and could access Victim’s laptop with full escalation privileges. See figure 4 below for the attempts, figure 5 for the completed and successful recovery.

Figure 4 – Password Recovery attempt using Cain and Abel

Once the lab was prepared, the investigator removed Victim’s laptop from the storage locker, provided power and attempted to boot the laptop. The laptop required a password. The investigator utilized the Caine and Abel software version 4.9.56 to recover the password. The first attempt involved the use of a dictionary to identify the password, unfortunately this was not successful. The next attempt utilized a brute-force process and after 5.5 hours, the investigator successfully recovered the password and could access Victim’s laptop with full escalation privileges. See figure 4 below for the attempts, figure 5 for the completed and successful recovery.

Figure 4 – Password Recovery attempt using Cain and Abel

Figure 5 – Completed and Successful recovery of Victim’s password

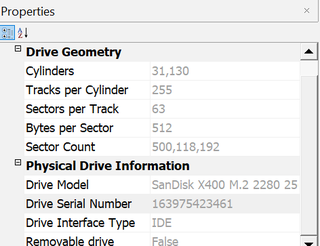

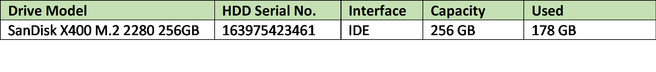

Accessing Victim’s laptop allowed the investigator to create a clone of the laptop’s hard disk drive (HDD). The HDD serial number that is associated with Victim’s laptop is 163975423461. This was obtained by mounting the lab PC to Victim’s laptop. The lab utilized AccessData’s Forensic Toolkit (FTK) version 3.4.3.3 to identify the details of the HDD.

Figure 6 – identifying the serial number of the HDD associated with Victim’s laptop

Figure 6 – identifying the serial number of the HDD associated with Victim’s laptop

Figure 7 - Additional Details about Victim's HDD Found in her Laptop

Analysis

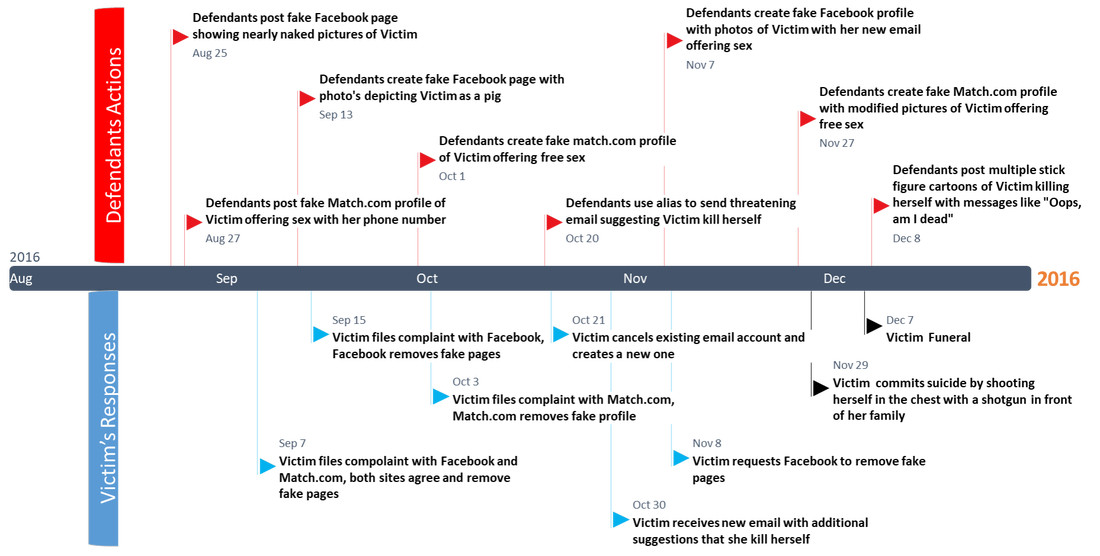

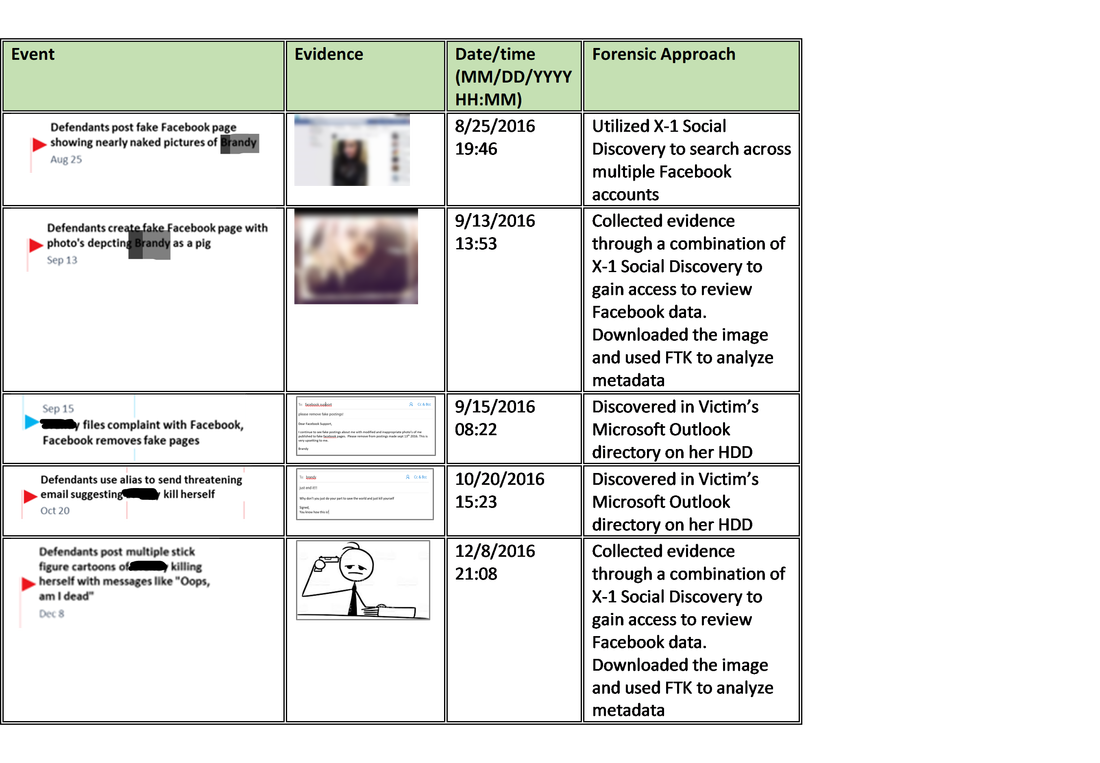

The timeline below (Figure 8) summarizes the actions initiated by the defendants (in red) and Victim’s responses (in blue). The dates range from August 25th, 2016 to December 8th, 2016. The investigation revealed multiple, unprovoked actions by the defendants to harass Victim through a number of social media sites and email. In all cases, Victim made every attempt possible to remove the fake postings by the defendants. The digital evidence suggests through her temporary log file found on her computer, she responded immediately from the time she opened the Facebook page, Match.com site or received an automatic notification from either of these sites. In every case, Facebook and Match.com removed the fake postings until Victim was no longer capable to respond due to her taking her own life on November 29th, 2016. The fake postings continued two days after hear death, with cartoons of Victim holding gun with statements regarding her suicide like “Oops, am I dead?”. Victim’s family discovered these postings several days after her funeral, notified the social media sites and request they be removed.

Figure 8 - Timeline of events leading to Brandy’s suicide

The timeline below (Figure 8) summarizes the actions initiated by the defendants (in red) and Victim’s responses (in blue). The dates range from August 25th, 2016 to December 8th, 2016. The investigation revealed multiple, unprovoked actions by the defendants to harass Victim through a number of social media sites and email. In all cases, Victim made every attempt possible to remove the fake postings by the defendants. The digital evidence suggests through her temporary log file found on her computer, she responded immediately from the time she opened the Facebook page, Match.com site or received an automatic notification from either of these sites. In every case, Facebook and Match.com removed the fake postings until Victim was no longer capable to respond due to her taking her own life on November 29th, 2016. The fake postings continued two days after hear death, with cartoons of Victim holding gun with statements regarding her suicide like “Oops, am I dead?”. Victim’s family discovered these postings several days after her funeral, notified the social media sites and request they be removed.

Figure 8 - Timeline of events leading to Brandy’s suicide

Figure 9 below highlights details associated with several of the events depicted on the timeline above. In most cases, the sources of the digital images (photographs) were easily identifiable through metadata tagged on the files. Little was done by the defendants to disguise or cloak the images origin. In some cases, the defendants attempted to create alias emails in an attempt to conceal their true identity, however, this was easily defeated through remedial forensic methods and tools.

Figure 9 – Notable events leading to Victim’s suicide with forensic methods taken

Figure 9 – Notable events leading to Victim’s suicide with forensic methods taken

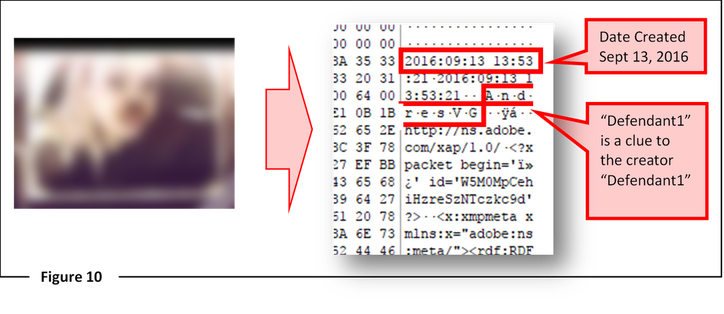

Figure 10 – Forensic approach example of extracting metadata from a digital image (photograph)

In this example, Victim had posted an original photograph of herself to her legitimate Facebook account. The perpetrators downloaded the photo, modified it, then reposted it to a fake Facebook page. The modified photograph was obtained through the investigation of the Victim’s HDD. In one of the threatening emails sent to Victim, the defendants included the modified photograph. Once obtained, the investigator analyzed the image for its underlying metadata. The underlying metadata exposed a number of facts regarding the photograph. Two are highlighted in this example (the complete data set will be provided at a later date). The first is the creation date of the file as 2016:09:13 which translates to September 13th, 2016. Second is the “Origin Authors”, this perfectly corresponds to the Exif.Image.Artist key in JPEG files, specifically at Tag HEX location 0x013b (Meta Reference Table, 2015). The value in this field is “AndresVG”; this alone does not prove to be the defendant. However, the investigator discovered a number of emails that were sent by one of the defendants to Victim signed “Defendant1” when the two were dating several months prior to this incident. This fact was immediately presented to the prosecutor (ADA) and he successfully used this to obtain a subpoena to gain access to the defendant’s Facebook account. The defendant’s Facebook account activity showed numerous submissions of Victim’s modified photographs and the creation of fake Facebook accounts. This was decided by the Texas State Court of Appeals in Tienda v Texas where the state presented evidence obtained from the Myspace profiles themselves (posts, music, photos, messages), which linked appellant (circumstantially) to the Myspace profiles (RONNIE TIENDA, JR., Appellant v. THE STATE OF TEXAS, 2012).

Recommendations and Findings for the Court - From the Investigator

In conclusion, the results of my analysis of the victim’s laptop and media storage accounts, conclusively demonstrates a sustained and systematic effort by the perpetrators reasonably calculated to induce Victim to harm herself. The perpetrators frequently subjected Victim to unwanted, negative and harassing messages and suggestions that she was unworthy, overweight, unlovable and unsalvageable. These negative messages from these perpetrators far outweighed in frequency and intensity any positive messages that she received from them or anyone else. My recommendation is the court admit my testimony and the content of the images, text messages and emails discovered within Victim’s devices and off-line media accounts.

Recommendations and Findings for the Court - From the Investigator

In conclusion, the results of my analysis of the victim’s laptop and media storage accounts, conclusively demonstrates a sustained and systematic effort by the perpetrators reasonably calculated to induce Victim to harm herself. The perpetrators frequently subjected Victim to unwanted, negative and harassing messages and suggestions that she was unworthy, overweight, unlovable and unsalvageable. These negative messages from these perpetrators far outweighed in frequency and intensity any positive messages that she received from them or anyone else. My recommendation is the court admit my testimony and the content of the images, text messages and emails discovered within Victim’s devices and off-line media accounts.

References

Digital Forensics Analysis Report Delivered to Alliance Defending Freedom , 1 (2015) (testimony of Coalfire Systems, Inc. ).

Cobb, C. (2009). Chapter 73 Expert Witnesses and the Daubert Challenge. In S. Bosworth, M. E. Kabay, & E. Whyne (Authors), Computer Security Handbook (6th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 1-7). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Forensic Readiness Checklist. (2013, March 11). Retrieved July 08, 2017, from https://carolinacrimereport.wordpress.com/civil-rico-checklist/forensic-readiness-checklist/

Kenneally, E., & Brown, C. (2005, August 19). DFRWS 2005 USA New Orleans, LA (Aug 17th - 19th). Retrieved July 8, 2017, from http://www.dfrws.org/sites/default/files/session-files/pres-risk_sensitive_digital_evidence_collection.pdf

Marcella, A. J., & Guillossou, F. (2012). Cyber forensics: from data to digital evidence. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Metadata reference tables [Table]. (2015, October 13). Exiv2.org.

Patil, P. S., & Kapse, A. S. (2015). Survey on Different Phases of Digital Forensics Investigation Models. International Journal of Innovative Research in Computer and Communication Engineering, 03(03), 1529-1534. doi:10.15680/ijircce.2015.0303018

Poland, A. (n.d.). What Is a Safe Temperature to Store a Hard Drive? Retrieved July 08, 2017, from http://yourbusiness.azcentral.com/safe-temperature-store-hard-drive-22204.html

Sammons, J. (2015). The basics of digital forensics: the primer for getting started in digital forensics. Waltham, MA: Syngress.

The State of Texas vs. Andres Arturo Villagomez, 1 (The County Court at Law No. 1 of Galveston County, Texas March 16, 2017).

The State of Texas vs. Karinthya Sanchez Romero, 1 (405th District Court of Galveston County, Texas March 16, 2017).

The National Archives; Digital Continuity to Support Forensic Readiness, 2011, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/information-management/forensic-readiness.pdf

RONNIE TIENDA, JR., Appellant v. THE STATE OF TEXAS, 2 (N THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEALS OF TEXAS February 8, 2012).

United States v. McClure (United States Court of Appeals, Eighth Circuit. August 1, 2003).

Vacca, J. R. (2014). Managing information security. Waltham, MA: Syngress.

Von Solms, S., Louwrens, C., Reekie, C., & Grobler, T. (n.d.). A CONTROL FRAMEWORK FOR DIGITAL FORENSICS. Retrieved July 8, 2017, from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7615/035a55f0bda1b48e624c73589f6827677fc2.pdf

[1] The contents of this report are considered historical fiction. Research was performed to understand the key elements and many of the aspects of the case like the people, places and events. However, all of the tables, figures, exhibits, illustrations and evidence is entirely fictional and invented by the author.

Digital Forensics Analysis Report Delivered to Alliance Defending Freedom , 1 (2015) (testimony of Coalfire Systems, Inc. ).

Cobb, C. (2009). Chapter 73 Expert Witnesses and the Daubert Challenge. In S. Bosworth, M. E. Kabay, & E. Whyne (Authors), Computer Security Handbook (6th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 1-7). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Forensic Readiness Checklist. (2013, March 11). Retrieved July 08, 2017, from https://carolinacrimereport.wordpress.com/civil-rico-checklist/forensic-readiness-checklist/

Kenneally, E., & Brown, C. (2005, August 19). DFRWS 2005 USA New Orleans, LA (Aug 17th - 19th). Retrieved July 8, 2017, from http://www.dfrws.org/sites/default/files/session-files/pres-risk_sensitive_digital_evidence_collection.pdf

Marcella, A. J., & Guillossou, F. (2012). Cyber forensics: from data to digital evidence. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Metadata reference tables [Table]. (2015, October 13). Exiv2.org.

Patil, P. S., & Kapse, A. S. (2015). Survey on Different Phases of Digital Forensics Investigation Models. International Journal of Innovative Research in Computer and Communication Engineering, 03(03), 1529-1534. doi:10.15680/ijircce.2015.0303018

Poland, A. (n.d.). What Is a Safe Temperature to Store a Hard Drive? Retrieved July 08, 2017, from http://yourbusiness.azcentral.com/safe-temperature-store-hard-drive-22204.html

Sammons, J. (2015). The basics of digital forensics: the primer for getting started in digital forensics. Waltham, MA: Syngress.

The State of Texas vs. Andres Arturo Villagomez, 1 (The County Court at Law No. 1 of Galveston County, Texas March 16, 2017).

The State of Texas vs. Karinthya Sanchez Romero, 1 (405th District Court of Galveston County, Texas March 16, 2017).

The National Archives; Digital Continuity to Support Forensic Readiness, 2011, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/information-management/forensic-readiness.pdf

RONNIE TIENDA, JR., Appellant v. THE STATE OF TEXAS, 2 (N THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEALS OF TEXAS February 8, 2012).

United States v. McClure (United States Court of Appeals, Eighth Circuit. August 1, 2003).

Vacca, J. R. (2014). Managing information security. Waltham, MA: Syngress.

Von Solms, S., Louwrens, C., Reekie, C., & Grobler, T. (n.d.). A CONTROL FRAMEWORK FOR DIGITAL FORENSICS. Retrieved July 8, 2017, from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7615/035a55f0bda1b48e624c73589f6827677fc2.pdf

[1] The contents of this report are considered historical fiction. Research was performed to understand the key elements and many of the aspects of the case like the people, places and events. However, all of the tables, figures, exhibits, illustrations and evidence is entirely fictional and invented by the author.